Who Is A Music Strategy For and What Should It Cost?

Are We Devaluing Ourselves? My ongoing series exploring what a global music policy could do...

There has been a boom in cities and places investing in music strategies. There are several hundred cities and communities compiling data to better understand music in urban policy. With this have emerged local music boards, municipal heads of music, state, province and canton music offices and a recognition that investing in music policies matters. This is welcome, but it’s a start. While there may be hundreds of communities doing this, there are over 4000 cities with over 100,000 people in the world. And of this work, there is no overarching framework that outlines, empirically and without prejudice, what works, what doesn’t and how much it should cost. This is what this post focuses on.

There are different approaches to doing this work with different levels of efficacy. From grassroots activism to city council resolutions - think one as bottom-up and the other as top-down, there’s little consensus as to what works best and why and what it’s worth. Many are one-offs, despite all policy work being a process (once you start, stopping negates any advancement). So could we create a standard set of practices and cost estimates, ones of course, that can be adapted for local realities and GDP? Similarly to my call to foster this scholarship in higher education (which is being adopted at the University of Aberdeen by Christina Ballico), I think so. Therefore, what would be the best path to take here?

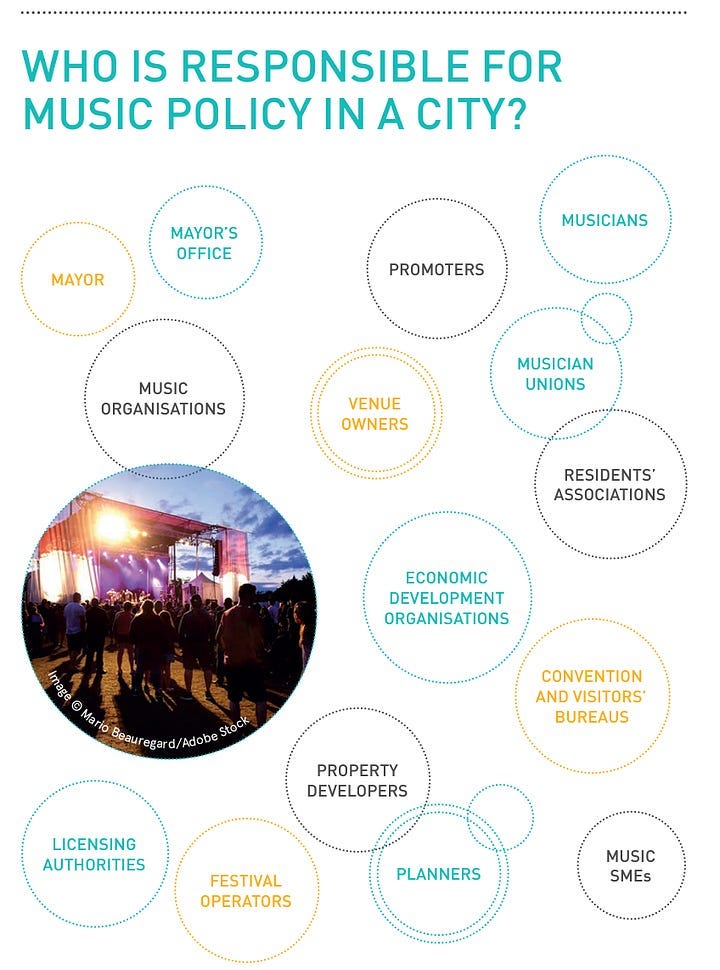

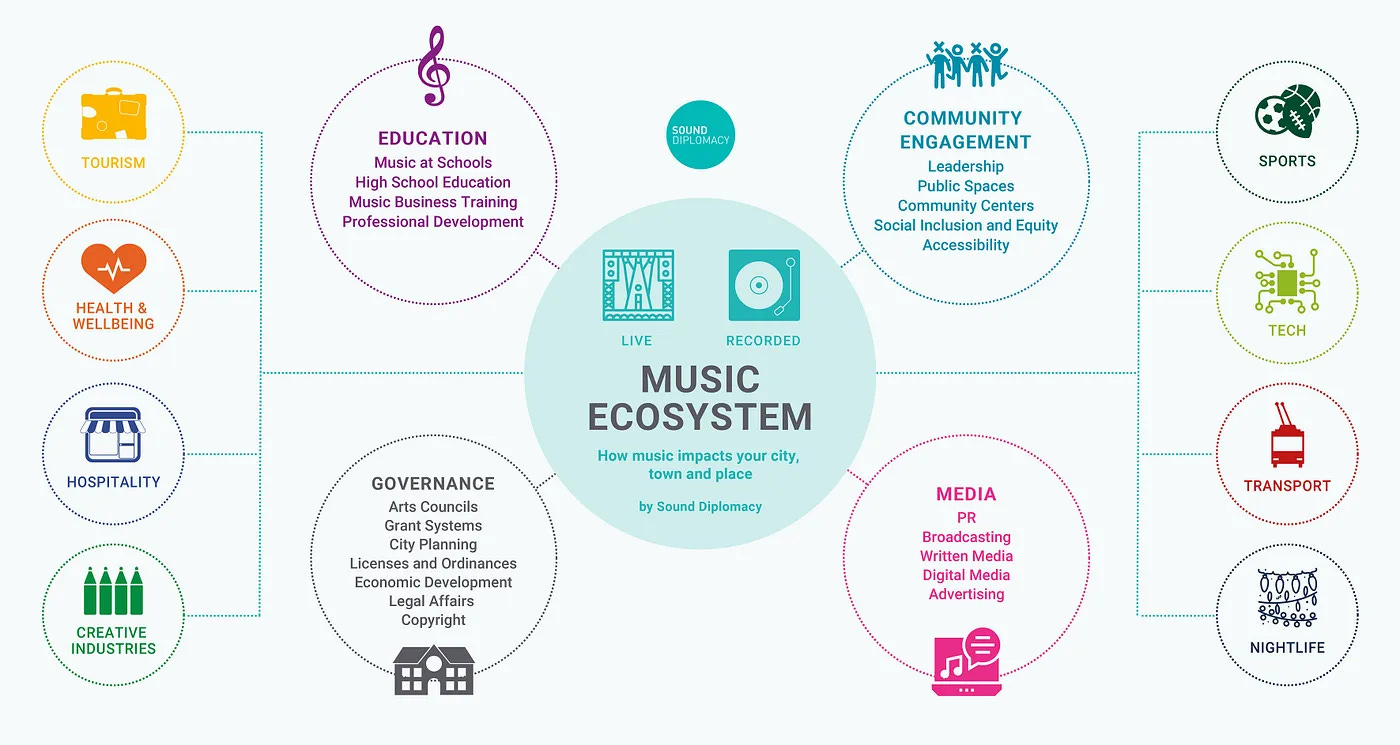

In 2016, Sound Diplomacy published the Music Cities Manual. The image above is from that (and the one below is from a few years later). Both images are still salient.

But are music strategies written for all of these constituents? Can one be written for all at once and if so, would that difficulty require more time, effort and expertise (i.e. cost)? I believe the answer is yes, and any framework must start here. The best work - work that lasts - appeals to as many stakeholders as possible outside of music, as much as inside. It starts with a different approach. If you’ve heard me speak, I outline an analogy involving a hammer and nail. If a music strategy is for everyone above, then music must be a nail, and everything else a hammer. Therefore, investing in music for music’s sake primarily (understanding the circumstances of musicians and the music ecosystem to articulate music-specific solutions) presumes that if music is a hammer, every nail is also music.

This is where I feel the rubber hits the road and we must ask - what is this worth to us and how much should it cost to determine the following: Can music make us healthier? Can music address global poverty or the climate emergency? Can music foster equitable city planning laws and codes? Can music stimulate economic growth? How do we make this happen and ensure it is aligned with existing policies, practices, and politics?

If we answer these questions, we will unleash the true impact of a music strategy on a place. And of course, none of this is successful if musicians are not counted, valued and remunerated for their work. I wish that went without saying, but it must be said. Without the art, there is no economic or social benefit.

Still, we live in a world that chronically undervalues arts and culture and sees it as a public good, not both a public good and an economic good. And this is where I believe, many working in this field play into these realities rather than challenge them. There is work commissioned - time and time again that at its very core - devalues music. One gets what one pays for. If we believe music should be free or cheap, this is what it is worth. We invest in what matters (I wish equitably, but that’s for another post). If understanding one’s music ecosystem is worth $15,000 or $20,000 (when similar studies to understand other key pieces of civic infrastructure are 4 or 5 times that), then it is not worth $150,000 or $200,000. And then we complain that music education, grassroots infrastructure, or copyright is undervalued, or under threat. This is so prevalent that a few of those whose job it is to expand the value of music argue that there should be a cap on what it is worth to understand. Who else devalues themselves in this way?

If modest sums are invested to compile data on musicians, for example, it should be seen as the start of a process. All policy is to begin, and commit to, a process. Therefore, would it be worth setting a baseline as to what this work should cost? Could a framework that defines a global music policy do that? Maybe we benchmark other sectors. How much investment is made in film commissions? Or sports commissions? Or public parks? Or football pitches? Is music worth the same as these?

As part of the development of a global music policy and the research at the Center for Music Ecosystems, I am working on this. For example, we partnered on research with Whippoorwill Arts, a California nonprofit, producing fair pay scales for a particular constituency of musicians.

If we continue to ask and answer why music matters to dozens of other sectors’ economic and social goals - including economics, health, education, infrastructure, planning, international development, and so on, we will realize that music, and musicians, are worth far more. The more we say, or accept, that music is not worth the money, it won’t be.

More cities doing this work is great. Doing it without sustained investment may not be over time. A global framework may help articulate this value differently and show, rather than tell, why music - and musicians, venues and everything in between - are worth far more. Remember, music is one of the things that we may not need to live, but would struggle to live without. I think that’s worth sustained, expansive investment to understand, safeguard and grow, everywhere.

Don’t you?

Good but disturbing read Shain. On a positive note there seems to be a groundswell of realisation in the UK. The Guardian covers this area regularly and The Music Venue Trust are doing a great job in lobbying the Government. Music is life.