What I've Learned In 10 Years Since The Launch of Music Cities Convention

A decade of music policy and where I feel we can go from here

In 2014, a friend of mine, concert and festival promoter Martin Elbourne (the 77th most important person in the music industry), published a report with the non-profit Don Dunston Institute in South Australia, titled The Future of Live Music in South Australia, with some terrific music policy advocates (Becc Bates, Joe Hay, and others). Martin also managed The Great Escape Festival in Brighton. I wrote about our plans in my book (available HERE). At the time, I was contracted to produce Canadian Blast, then the largest country-specific showcase at the festival (and at one point a CD that came with an NME issue - see below.) I was a fan of Martin’s report and asked if we could partner up to sell his services to more cities. So we tried.

But few folks cared, so we decided, together, to hold a conference on the topic, which we titled the Music Cities Convention in May 2015. We did not invent this topic. The Responsible Hospitality Institute had been writing about music policy since 2004. IFPI’s Canadian affiliate wrote a report, The Mastering of a Music City, in 2014, which was based on exchanges between Toronto and Austin. However, we had a festival partner, and people were coming anyway, so we asked friends around the world to join for free lunch and a nice chat. And the rest, I guess, is history.

That event, looking back, changed my life.

Before, I worked in music export, with a background of music journalism, PR, and a general ‘whatever I could get paid to do in music’ attitude. After, I had a niche and, looking back, a sense of purpose. And I’ve learned a lot.

As we prep for the 10th anniversary event in Fayetteville, Arkansas (and the first I won’t be at, unfortunately), here are some thoughts and observations on this whole world of ‘music cities policies’.

Please do comment below if you have any thoughts, disagreements, or any memories from attending one of the events. I’d love to hear from you.

Music Cities Policy - Observations

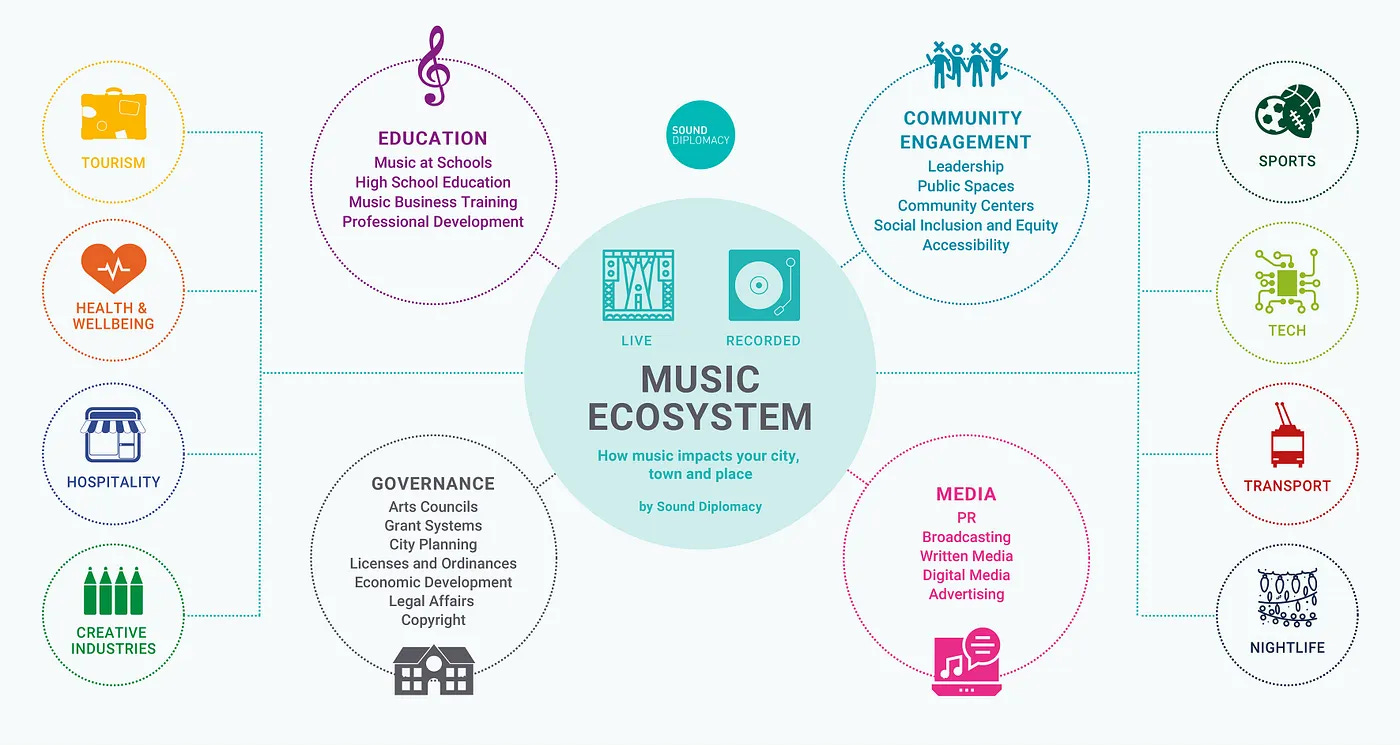

THE BEST SOLUTIONS ARE NOT MUSIC BASED - Most issues that impact music in cities have little to do with music, and those whose experience lies in the music industry often lack the skills to solve them. I see it time and time again. The idea is that if you explain a particular issue facing musicians or other stakeholders in the music industry (venue owners, for example) and outline a solution that comes from the perspective of said constituents, the chances of the problem being solved decrease. People care deeply about music. I have had countless conversations with politicians and policymakers outlining their love of music. But a love for music doesn’t necessarily correlate with a recognition that musicians also matter. I have had far more success tying a particular issue impacting a particular music ecosystem to a broader community problem - jobs, health and safety, regeneration, competitiveness… But I am no expert in creating jobs in a place. Nor are music policy advocates.

MAKING MUSIC SPECIAL DOESN’T WORK - The more music is seen as special, otherworldly, or exceptional in communities, the harder it is to advocate for it. When music is seen as special, rather than simply another policy area that requires robust apolitical due diligence, data, and research, everyone’s individual version of what special is gets in the way of nuts and bolts reforms that are needed to build in, rather than bolt on, good music ecosystem policies. Instead, I often see people thinking with their hearts about music, rather than with their minds, and in doing so, music is elevated to something different. To me, this means that from a policy perspective, it becomes difficult and expensive.

COVID SHOULD HAVE BEEN A TURNING POINT - The pandemic should have elevated music’s impact. I’m not sure it has. We had to migrate our events online during the pandemic, as everyone else did. It was incredibly difficult, but one thing the pandemic demonstrated, every day, was how important music was to all of us. I believe it is the best case study we’ll ever have to demonstrate why music matters, and I thought we’d come out of it with a newfound value proposition that would take hold in places, now having the experience of a life without live music and music-related events. Yet, what I believe is happening is the great forgetting. Now that music is back, the amount being invested in safeguarding music ecosystems is declining, which I think can also be correlated with accelerated political polarization and distrust. If a community believes that it can support its music ecosystem for the same cost as a trade booth at an economic development conference, I believe the value proposition argument is moving backwards. This is making it more difficult to insulate a music ecosystem from shock. And it again, exceptionalizes music, rather than incorporates it as a priority economic sector alongside others.

MUSIC INDUSTRY & MUSIC ECOSYSTEM ARE DIFFERENT, BUT INTERTWINED - The needs of local music ecosystems and the commercial music industry are different but intertwined. We need both to thrive. The statistic from Music Business Worldwide, as outlined by Deezer yesterday, that 30% of music uploaded onto its platform was AI-generated, and much of it done fraudulently, demonstrates the challenges the commercial music industry faces in convincing all that human artistry and creativity are what matters. Yet, on the face of it, more AI music uploaded onto DSPs doesn’t impact the existence of a local music school, a music therapy program at a social care facility, or a choir to combat loneliness. Yet, I don’t think we have done enough to link the two together and recognize that it is at home, in our communities, where the belief that human artistry matters is instilled into us. I think more work needs to be done to bring these two sides together, because it impacts everyone, everywhere. For example, I wonder how Young Voices, the world’s biggest children’s choir, is instilling a belief in every child that AI music is not, and never will be, the same as human-made music. If the music industry flatlines, there will be fewer opportunities locally. If local programs are reduced, so does the talent pool. I don’t believe we have yet to reckon with how to articulate and build data sets around this coupling. This is an opportunity.

THE PAST IS THE PAST. WHY ARE WE OBSESSED WITH IT? We Are Increasingly Being Lulled By Nostalgia, And That Worries Me. I’m thrilled that the Oasis tour was a success. I’m also thrilled that Paul Simon is back touring. Same with Van Morrison, Bob Dylan, Shania Twain, Belinda Carlisle, or Rod Stewart. All of these shows create jobs, experiences, moments, and memories. However, obsessing over nostalgia is leading to a lack of action to address the challenges currently facing us and those that will arise in the future. The average age of festival headliners continues to increase. Grassroots music venues continue to struggle because we have yet to create a supportive land-use framework to safeguard them as community assets, like libraries or healthcare centres. The cost of pursuing music professionally is out of reach of many, leading to a sector that is only open to those who can afford it. We laud and celebrate big stadium concerts in the UK, forgetting that in most countries in the world, the simple act of touring is impossible. Ed Sheeran’s world tour hit an incredible 43 countries. That’s 1/5th of the world, and only possible because he has the resources to do so. Music education remains a privilege, not a right. There are 47 countries with no copyright infrastructure of any kind, meaning pursuing a career in music in them means you have to leave. Very few cities that saw the economic bump that Taylor Swift brought have done anything to better regulate their music ecosystems. Yet, the more acts from the past reform and offer experiences to allow us to go back in time to when things were different, the less these current issues are recognized. To me, that’s a missed opportunity

WE NEED TO STOP SEPARATING CULTURE AND ECONOMICS. Those Separating Cultural and Economic Objectives Are Wrong. There is a rhetoric that pervades, arguing that focusing solely on numbers, jobs, and economic data devalues a music ecosystem. Doing so depreciates the inherent cultural value of music and turns those creating it into commodities. I think this belief is incorrect and peddled by those who lack the understanding of how to use economic data to better protect and preserve cultural goods. Decisions are made using dollars and cents, or pounds and pence, in communities. I wish it were different, but that's just the way it is. If we don’t understand how music functions as an economy in a place, it is harder to advocate for it as an economic good. And decisions will be made regardless of what to invest in, prioritise, or defund. You can have both at the same time. Economic data can be used to advocate for cultural protection. When it’s absent, I believe decisions are more inequitable, because someone has to choose whose culture is worth protecting. To me, more data that is agnostic and scrutinised helps facilitate better decision-making. And while there are some that believe this doesn’t matter, because of the innate cultural value of music, I’d ask - how are we doing in general? Is intellectual property safeguarded around the world? Are musicians being treated fairly by everyone and remunerated for their work adequately? Is cultural heritage protected everywhere? Do communities invest in culture equitably, everywhere? If any of these answers are no, I posit a simple question… why then? To me, economic data, if robust, is a tool to safeguard cultural value. But it has to be contextualized, explained, and articulated so as not to frame music as a commodity or an asset. I also recognize that I may not always be the right person to deliver this data, depending on the place, but I acknowledge the need for the data to exist. This false dichotomy, to me, leads to bad policy, which makes life worse for culture bearers. Also, and more questionably, it can be argued that those advocating for ignoring economic data because it depreciates in cultural value are often those who live in a world of privilege that allows them to separate the two, because they can. After ten years, this continues to bother me because it’s wrong. Anyone who tells you to ignore the need to have robust economic data to advocate for music ecosystem policy is misleading you.

PERSISTENCE IS THE BEST STRATEGY: I read a post from

, reminiscing on when the Music Venue Trust was created in 2014. I worked with Mark (and his wife Bev, who is the real force here) at the time when she coined the term Grassroots Music Venue, which then meant nothing. Ten years on, the ‘Agent of Change’ planning guidance to help support venues and entertainment spaces is still not law in the UK. It remains, frustratingly, guidance. But they have been at it for a decade and are still here, and are now celebrating artists and venues voluntarily committing to a French-style ticket levy to help support a phrase - and community - that didn’t exist a decade ago. Moreover, I have seen networks grow and assert themselves, including the EU-based Music Cities Network, which has expanded, alongside the now 60 cities in the UNESCO Cities of Music Network. The Mayor of London, for example, continues to operate a robust music and night-time economy policy team that consistently fights for music and NTE policies across the capital. There are thousands of advocates I have met, each of them impressive in their own right, who refuse to let music, club culture, or music education be ignored or defunded. I’ve realized in this world, existence and persistence are a form of success. Politicians change. Priorities change. Keeping music ecosystem dialogue current in cities is hard. There are so many people who deserve to be recognized for the work they do in this space (which is why we set up the Music Cities Awards, of course), and many, ten years on, I owe a debt of gratitude to.LASTLY, THERE’S MUCH TO BE HOPEFUL ABOUT. I think that we have an opportunity to create a golden age for music ecosystem policy. More cities are engaged than ever before. There is more data and best practices than ever before. Music tourism is as popular as ever. More people are listening to music than ever before. The music industry continues to increase in value (albeit slower than a few years ago, but it is still growing, especially in so-called emerging markets.) These are all positive signs. This is why I’m excited about learning from the debates and conversations that happen at Music Cities Convention.

Yes, there are multiple threats - geopolitical, AI, and environmental - but the increase in activity over the last 10 years, looking back from when Martin and I had a beer in London and first discussed the idea, is encouraging. But we have a lot to do.

Thanks for reading, and curious what you think. And thank you to anyone in the Music Cities space who has reached out, shared their passions with me, and worked with me anywhere - be it attending a roundtable, hearing me speak, responding to an article… There are too many of you to count, but I want to be clear - I recognize how lucky I am to be able to do this work, and that’s down to all of you. Onward and upward.

Love this quote:

"In this world, existence and persistance is a form of success"

I'm sure this phrase can help soothe the minds of lots of music advocates.

It also reminds me of something that Andrew Mosker mentioned: turning a city into a "music city" is a long journey, one that starts to really shows its results in a 10-20 year span and it's never a finished process.

Thanks for this 10 year round up with lessons from the Music Cities Convention!

So many ideas and links to resources to keep thinking about music in cities.

Just what I needed to light up my Friday!

Thank you, Shain, your inspiration always fuels my aspirations.